Once again, it's been a while so let's get in on this.

There are twelve plates for this rule. I'm going to end up grouping some of them

together, because they're a pretty clear progression through the whole action.

It's a bit different than how I've done this previously, but I think it'll make

sense once they're all lined up.

Interestingly, along with the first picture, Fabris brings up one of the

problems that we can very easily run into when examining plates in manuals.

Specifically, that they are snapshots in time, and not necessarily moments to be

held. "In the illustrations, it may seem that our fencer, after performing a

transverse step, is waiting for a tempo; but this was done only to show the

position of the foot, body, arm and sword. In real life, all of this should be done quickly and without pause." This is an important thing to keep in mind with most plates, but perhaps especially when we're looking at Book Two, where the entire point is that we should be in constant motion.

So as we begin, plate 130 shows us on the right. Our left foot had landed almost in measure, so we've stepped off-line out to the right, and we're leaning over our right foot as we go. Note that at this point, our sword is still supposed to remain just underneath our opponent's sword. Fabris says that this will make it more difficult for our opponent to find and so they'll hesitate. That may be true, but there's another point to it that we'll see in a little bit.

Anyway! We flip to the left side for plates 131 and 132. I find 131 particularly interesting because if you look closely, our left foot is already off the ground and moving. It's slight, but it's there - the shadow underneath the foot gives it away. Here, as our opponent hasn't moved, we're picking up our left foot to pass forward "along the line of [our] opponent's sword" while at the same time closing out the line to the inside by beginning to turn our hand into quarta. At this point, if our opponent continues to do nothing, we move right into plate

132, where we have finished the pass forward and have

wounded them. Fabris notes that by now, the only options our opponent has

available are to parry and retreat, but that's simply too little, too late.

Before we take a quick look at the other possibilities that Fabris mentions

could have branched out from the ones that are illustrated here, I want to

point out a couple things from plate 132. Notice just how squared off we are

in there - start with the hips and look both up and down. There's some

profiling in the shoulders, and the positioning of the left arm supports that,

but that really just seems to be the final moment of structuring your

shoulders for a good quarta and a little more reach. Looking at the hips and

legs, we are overall in a very squared off position. The hips are almost

completely square to our opponent, with only just enough right hip leading to

maintain body structure on the attack. The feet are not remotely in line with

each other, either.

How could that have gone differently, though?

If back during plate 130, our opponent could have followed our body with the

point of his sword. If they did, we lean off over the other foot which has the

additional impact of allowing our sword to more easily close out our

opponent's sword, which should now be pointing in the wrong direction. We

rapidly follow that with another step, and that's pretty much that.

Around the point in the process where we see plate 131 our opponent could try

to cavazione, in which case we can "bring [our] right foot on the line with

the left and wound [our] opponent in third" which works in part due to the

additional breadth and the geometry caused by the body lean off to the

side.

The next set of three plates shows us what happens if we had initially moved to the other line. In this case, we're leaning off over our left foot because we initially landed on our right. From there, the process proceeds in essentially the same sequence as the previous one, just on the outside rather than the inside. (As a note, "our fencer" in the plates goes from the left, to the right, to the left here. I really wish that he had called that out in a more obvious way.)

As a note, Fabris once again relies on terza to be his outside guard. It's certainly faster than turning into seconda, but if possible we won't be touching our opponent's sword anyway. He notes that if we're not worried about blade pressure that we can just push through regardless. However, if our opponent moves to parry our sword we can - and say it with me - turn our hand into seconda and wound them underneath their blade. If instead they

cavazione, we'll just turn into quarta and continue straight in with our left foot. If they cavazione later in the process, around the plate 135 stage, we'll also turn into quarta but catch them before they even finish the cavazione and wound them anyway.

Fabris wraps up this sequence of plates by noting that once we are in a place where we're capable of wounding our opponent, the only option they have available to them is to try and break measure, whereas the fencer who is moving forward has a number of options available to them. This is a pretty common theme in Book Two - the idea that once you get sufficiently close to your opponent, and have maintained control over the engagement the entire way, there's a point where there's nothing that they can do about it except to try and retreat. If they do try to retreat, you just keep progressing toward them, effectively replaying the last step of the progression again and again. It certainly has a different look and feel to more typical engagements, where the "there's nothing you can do here" portion of the fight happens later in the play and doesn't last for as long.

Next we have plate 136. Here we see what happens if we initially step off the line with our left foot, and our opponent follows our body's lean with the point of their sword. Remember that our blade was in line directly underneath theirs, so to close out their blade to the inside, all we need to do is

slightly raise ours. Here it was brought straight up such that the guard rests on our opponent's blade, which has the convenient side effect of completely closing them out with minimal movement on our part, and by placing our guard directly onto their blade, which is really the ideal way to have blade contact if you have to have it. If our opponent draws back and attempts a parry, we will perform the unsurprising action of turning to seconda around their parry. We lean back to the left to ensure that we can cleanly pass the point of their blade, and strike them as we go.

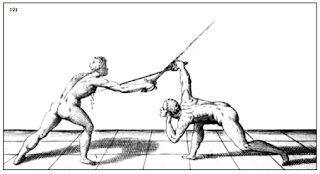

Plate 137 is also a single plate and not a sequence. Here we see what happens when our

opponent tries to turn into seconda and strike

us underneath our blade.

Here we began by stepping off-line with our left foot, leaning over it, and pushing forward with our right. We've placed our blade next to that of our opponent's which completely shuts them out to the outside. As we do that, our opponent turns into seconda and lowers their body as they attempt to strike us underneath our blade. The reason this doesn't work is because the movement of our blade is both incomplete and minimal - we're not committing to a large movement. Additionally we are already in motion forward, all we need to so is to lower our blade and stay in terza. While we pass with our left foot, our body and arm lower as well. Comparing this plate to previous plates with a wound (132, 135, and 136) we can see that our arm is somewhat withdrawn. This is to keep our guard strongly on our opponent's blade to force it downward, with the pictured result.

Plates 138 and 139 are part of the same sequence, so we're grouping them up. This is an interesting setup that isn't

explicitly described earlier, but if you take a lot of implied instructions it lines up pretty well! In plate 138, we're in quarta underneath their blade, and you can see our left shoulder is running ahead of our right; we've already stepped off-line with our left foot and followed that with our right, and have moved our body over to the left. From here, if our opponent follows us, we'll wound them to the inside in

quarta, just like we'd expect. If they don't follow us, Fabris says that we'll wound them to the outside - but

over their sword while we're

still in quarta, which is what plate 139 illustrates.

As an aside, this serves as a good reminder of what Fabris means by "over" our opponent's sword. Here, as in plate 137, our guard is on top of our opponent's sword and is forcing it down and away. While yes, our blade ends up under our opponent's guard and arm as well, it is our guard which has the control in the situation; contrast that with plates 132 and 134.

Plate 139 is an excellent illustration of the sword being stronger in the direction toward which it points - which in the case of a quarta is towards the outside. Quarta closes the inside line, but the guard is stronger towards the outside. Similarly, seconda closes the outside line, but is stronger towards the inside. Angles, wrists, and physics are pretty great. Usually I'd want to turn into seconda to really close out that line, but we're already too close to have the time for that, and with our guard right on their blade, it's really not all that necessary.

Finally, we're down to plates 140 and 141. Here we have a visual depiction of what Fabris says to do if we're using this rule and our opponent assumes a very low guard. Fabris says that this doesn't require any "sudden movement" downwards of the hand, body, or feet - you're just moving yourself into position as you approach into measure.

Note how here we can see a depiction of Fabris' warning from the first section of this rule, how as we lower our guard, we need to be sure to leave the

point of our sword

above the guard of our opponent's. If we don't, you can now easily see how that would change the relationship between our forte and our opponent's debole, making it

much easier for them to cavazione, take control of our blade, and wound us.

Plate 141 is the result of the setup in 140 if our opponent doesn't do anything; we've turned into quarta. The only options for our opponent that could extend this play involve breaking measure, and raising their sword to parry. If they do this though, they'll likely bring their points off line anyway, and we can just use our body positioning to remain safe and wound them underneath their blade in seconda.

Whew. That was a lot of material to cover. We have two more rules for the sword alone, but for my next post, I think I'm going to take a break and go through the material we've covered so far and look for similarities, differences, common concepts, and how it all works. I think that looking at each rule as an individual flowchart is perfectly valid and honestly good - you can absolutely approach your opponent and decide as you're approaching which rule to apply - but digging a little deeper might show us something useful, or at least be an interesting exercise.